Back in 1991, as the Presidency of George H.W. Bush wound into its final year, and Canadians were still grumbling about Brian Mulroney and smarting that the Toronto Blue Jays had choked again in their third League Championship Series, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country made just shy of $100 million worldwide against a budget of $30 million and proved to the folks who track such things that Star Trek was a fairly dependable, if not exceptional, mid-grade box office earner. Its fans were a solid bloc who could be counted on to swarm the multiplexes in regular numbers every couple of years as long as there was something with the Trek name on it to entice them. As ’91 rolled into ’92, the movie series looked certain to continue, but the question was, with whom? Shatner, Nimoy et al were considered too old and too expensive now, and The Undiscovered Country had been deliberately designed to close the book on their adventures. With Gene Roddenberry dead and gone, and Harve Bennett alienated after his aborted Starfleet Academy project, the title of franchise guardian drifted to Star Trek: The Next Generation executive producer Rick Berman. He was approached in the middle of TNG‘s fifth season to begin planning for Star Trek VII, to feature Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) and his crew transitioning to the cinema. Paramount was not keen on releasing a movie while people could still watch new episodes of the show for free on television, so the series was capped at seven seasons, to conclude in the spring of 1994, with the movie to follow that same Christmas.

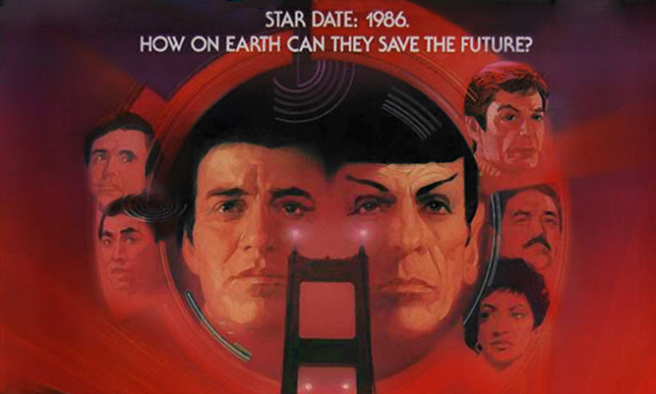

Berman wanted to include the original cast in some capacity to make this event a true passing of the torch, and for the story he commissioned two different scripts, written independently, from which he could select the best. Maurice Hurley, who had been the showrunner for TNG in its first two tumultuous seasons, penned one, while the prolific young team of Ronald D. Moore and Brannon Braga, who wrote TNG‘s series finale “All Good Things,” collaborated on the other. (A third was to be written by Michael Piller, but disliking being pitted against friends, he declined the invitation; Piller would write the screenplay for Star Trek: Insurrection four years later.) Moore and Braga’s script was the winner. Their original concept was based on an imagined poster of the two Enterprises battling each other, but, finding themselves unable to make that work, the duo instead came up with the idea of a mystery that would begin in Kirk’s time and end in Picard’s, with the character of Guinan (Whoopi Goldberg) – already established on the show as an enigmatic, extremely long-lived alien – as the link between the two. The movie’s prologue would feature the entire original cast (pared down through budget-conscious rewrites to only Kirk, Spock and McCoy), and then Kirk would return to team up with Picard at the film’s climax. Of course, that would depend on whether or not the old gang was up for yet another “last ride.”

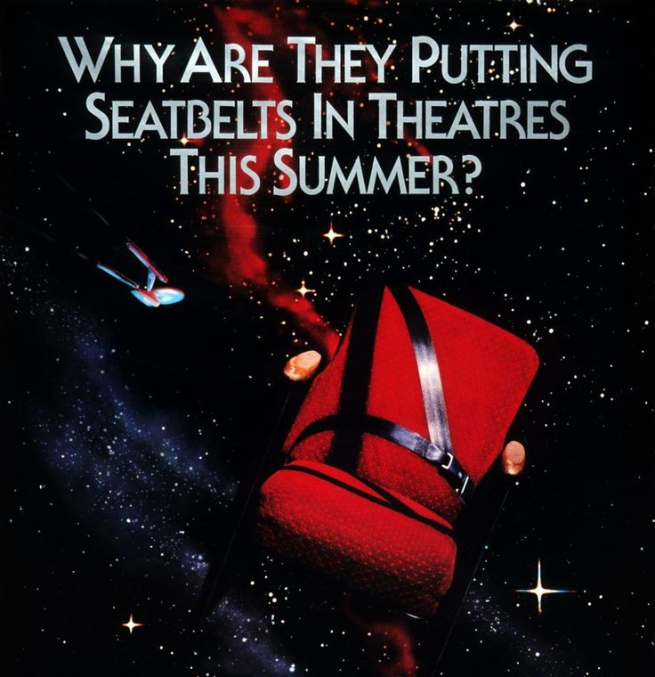

Leonard Nimoy was sent a copy of the script and presented with an offer to direct as well, given his sublime track record. However, this time Nimoy was not being invited to contribute to the story; he was being asked only to come in and shoot somebody else’s finished script, which were hardly his ideal creative circumstances. After all of his extensive proposed changes were vetoed by Berman, Nimoy declined both the top job and the chance to wear the pointed ears on camera again, citing that Spock didn’t serve much of a purpose in the movie. DeForest Kelley also turned Berman down, feeling that he’d already said his farewells in The Undiscovered Country. James Doohan and Walter Koenig were hired in their place and Scotty and Chekov were assigned Spock and McCoy’s respective lines (which is why Chekov is the one to take charge of the unstaffed sickbay in the prologue despite no hints he’s ever had medical training). But William Shatner was in, intrigued by the notion of playing Captain Kirk’s final hurrah, and admittedly flattered by Moore & Braga’s deliberate inclusion of several horseback riding scenes, Shatner being known for his love of horses and his expert riding skills. At the request of the studio for a dastardly villain to rival Khan (a recurring theme, you’ll start to see), A Clockwork Orange‘s Malcolm McDowell was enlisted as an alien mad scientist, and David Carson, who had helmed several acclaimed TV episodes including “Yesterday’s Enterprise,” and the two-hour pilot of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, was named the movie’s director. To help set it apart from its predecessors, the number VII was dropped from the title and it became Star Trek Generations.

To assist Carson, Berman brought most of the behind the scenes personnel from Star Trek: The Next Generation onto the movie with him, including line producer Peter Lauritson, production designer Herman Zimmerman (who had designed the last two Star Trek movies, so he was not entirely new to features), makeup designer Michael Westmore, costume designer Robert Blackman and composer Dennis McCarthy. Several actors and extras who had appeared in TNG as guest characters over the years were given bit parts in the movie, notably Tim Russ, the runner-up for the role of Geordi LaForge and the future Lt. Tuvok on Star Trek: Voyager, who played a human member of the Enterprise-B bridge crew. (Completing an interesting circle, Jenette Goldstein, best known as uber-tough space marine Vasquez in James Cameron’s Aliens, was cast as the Enterprise-B’s communications officer; during the development of The Next Generation, Vasquez had inspired the creation of the Enterprise-D’s security chief Macha Hernandez, who then became Tasha Yar when Denise Crosby got the part.) In fact, the only member of the lead crew with significant feature film experience (but no Star Trek experience) was cinematographer John A. Alonzo, who had received an Oscar nomination for lensing Roman Polanski’s classic Chinatown and had also shot such notable films as Harold and Maude, Norma Rae and Scarface. Alonzo’s list of credits was so long and his work so esteemed that he could get away with calling Shatner and Stewart “Billy” and “Patty” on set. He was hired to ensure that although this was essentially an expanded TV production made by TV people featuring TV stars, it would at least look as much like a movie as it possibly could.

Whether it felt like a movie was another matter…

In the late 23rd Century, Kirk, Scotty and Chekov are invited to the dedication of the U.S.S. Enterprise-B, under the command of freshman Captain Cameron Frye… er, John Harriman (Alan Ruck), and piloted by Ensign Demora Sulu (Jacqueline Kim), daughter of Hikaru. Kirk himself is invited to give the order to get underway, but he is feeling restless and out of place on a bridge that clearly no longer needs him. A few moments into the Enterprise‘s “quick run around the block,” a distress call comes in from two transport ships trapped in a strange, pulsing ribbon of energy that is traveling through the galaxy at high speed. Harriman’s inexperience leads the young captain to set pride aside and ask for Kirk’s help. Kirk advises the risky maneuver of moving the Enterprise into transporter range, where Scotty manages to beam forty-seven survivors aboard, including a wild-eyed man who pleads to be allowed to go back, and a silent, shaken woman we recognize as Guinan. The Enterprise is caught in the wake of the energy ribbon, and without photon torpedoes, the only chance to escape is to reconfigure the deflector dish to simulate a torpedo blast. Kirk volunteers to descend to the lower decks to carry out the last-ditch repair, and he succeeds in helping break the Enterprise free and clear – but a last charge from the ribbon blows apart the section of the ship in which Kirk was working, and he is sadly presumed lost.

Seventy-eight years later, the crew of the Enterprise-D is celebrating Worf (Michael Dorn)’s promotion to Lieutenant Commander on a high seas holodeck simulation when Captain Picard receives a message advising that his brother Robert and nephew Rene have been killed in a fire. The Enterprise also intercepts a distress call from a stellar observatory in the Amargosa system that is under attack. The only survivor is the same wild-eyed man who was rescued in the prologue: Dr. Tolian Soran (McDowell), a 300-year-old scientist who lost his family when his world was destroyed by the evil cybernetic Borg. Soran asks to be allowed to return to the observatory to complete an experiment he is running. Picard is reluctant until his crew’s investigation is finished, but Soran preys upon Picard’s obviously troubled feelings (“They say time is the fire in which we burn”). Aboard the observatory, android commander Data (Brent Spiner) and chief engineer Geordi LaForge (LeVar Burton) have uncovered some mysterious equipment hidden behind a secret panel when they are interrupted by Soran, who knocks LaForge out and pulls a weapon on Data. Data, having recently undergone the implant of a chip that allows him to feel emotions, is frightened into submission. Back on the Enterprise, an equally emotional Picard is confessing remorse over his lost family and his increasing feelings of mortality to ship’s counselor Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) when the Amargosa star abruptly goes nova. First Officer Riker (Jonathan Frakes) and Worf beam over to the observatory to rescue their comrades, but Data is scared and cannot help. Soran and LaForge are beamed away aboard a Klingon vessel that appears out of nowhere, the others return to the Enterprise and Picard orders it to warp speed as the shock wave from the dead star blows the observatory to atoms.

Soran has allied himself with the nefarious Klingon sisters Lursa and B’Etor, bargaining transportation and equipment in exchange for information on how to make a weapon capable of destroying stars. Guinan, who is from the same alien race as Soran, tells Picard that Soran’s true ambition is to return to the Nexus, a timeless dimension that is accessed by way of the mysterious energy ribbon and feels like being enveloped in perpetual joy. By destroying the Amargosa star, Soran has altered the ribbon’s course. It will pass through the Veridian system, and if Soran destroys the Veridian star, come into direct contact with Veridian III, allowing Soran to be swept into it since flying into it with a ship is impossible. However, the star’s destruction will obliterate the entire system and its population of two hundred thirty million. The Enterprise warps to Veridian, where the Klingon ship is already in orbit. Picard proposes a prisoner exchange whereby the sisters return LaForge and Picard agrees to be their hostage provided he can speak with Soran first. The Klingons agree, Picard heads to the surface, and LaForge is sent home – but the visor that allows him to see has been reprogrammed to transmit his field of vision to someone else. The Klingons use it to discover the frequency of the Enterprise‘s shields and begin firing directly through them, battering the ship irreparably. Our heroes manage to exploit a technological vulnerability and destroy their attackers, but not before the Enterprise’s warp core is critically damaged. While the saucer section separates safely, the explosion of the warp core knocks it out of orbit and sends it down to a spectacular crash landing on the planet’s surface.

Elsewhere, on a mountaintop on Veridian III, Picard attempts to talk Soran out of his plan, and when that fails, to fistfight him out of it, which also fails. Soran launches a probe into the Veridian star, which goes dark, and the energy ribbon blankets the mountain, whisking Soran and Picard into the Nexus just before the star’s explosion destroys the planet and what is left of the Enterprise with it. Picard awakens on an idyllic Christmas morning, with a loving wife and family and a very much alive Rene. The illusion is seductive given Picard’s recent losses, but he soon realizes that something is not right, and suddenly Guinan appears; an echo of herself left behind when she was beamed away in the prologue. Guinan explains that time has no meaning here, and Picard declares his intention to return to Veridian III and stop Soran – but he knows he can’t do it alone. Guinan’s echo can’t return, but she knows someone else who can: James T. Kirk, who survived the mission of the Enterprise-B after all. Kirk is also initially reluctant to leave the Nexus, where it seems that he can right all the wrongs he ever committed in his life, and have a future with a woman named Antonia whom he wished he had married instead of returning to Starfleet. But a leap on horseback across a gully that sparks no emotional response makes Kirk realize that the Nexus is an ultimately empty experience. He agrees to help Picard to try to make a difference one last time.

Time resets itself, the Enterprise crashes again, and the two captains emerge on Veridian III before its destruction, tag-teaming their wits and fists against Soran. Kirk makes a daring – and real – leap across a chasm to retrieve a control pad from a collapsing bridge, giving Picard the chance to reprogram Soran’s probe to destroy itself on launch, and take the mad doctor with it. The Veridian system is saved and the Nexus ribbon passes by harmlessly. But what finally defeats the seemingly immortal Captain Kirk is rusty steelwork and gravity, and Picard bids him a thankful goodbye as he contemplates the undiscovered country and whispers an awed “oh my” before breathing his last. Picard buries Kirk on a hilltop. Later, he and Riker comb the ruins of the Enterprise‘s bridge for Picard’s treasured family photo album, and Picard speaks of time not as a predator but as a companion who reminds us to cherish our memories. They beam away from the wrecked captain’s chair, and three starships carrying the survivors of the Enterprise careen away at warp speed to the triumphant sound of the Star Trek fanfare.

When I was fourteen, and Star Trek V had just come out, I tried writing a fan fiction story where Kirk and Picard’s crews would meet each other in a dimension outside space and time, and collaborate to defeat some Klingons and escape back to their respective eras. It was called Star Trek: The Two Generations, and I don’t mind admitting that it was pretty dang bad. I’d also be willing to bet that there were hundreds of fans just like me over the years prior to the release of this movie writing their own fan fiction versions of “Kirk meets Picard,” and no doubt the quality would vary from exceptional to barely literate. It is a great disappointment that this movie, written and assembled by the professionals, also feels like fan fiction, pegged squarely in the middle of that range. The best you can say of it is that it is competent, that it hits the marks you would expect it to hit, but it does so much like a puppy led by a leash from point A to point B, begging with wide eyes for an approving belly rub. The screenplay bears the obvious trait of the committee approach, resulting in so many mandated events to plod on through that nary a single scene has the chance to breathe and register any emotional impact.

Not that any scene would anyway, given that the arcs for our characters are perfunctory and come off as though they were written by people who have only studied emotions rather than felt them (a common issue with young screenwriters). In this series I have lauded the depth and literacy of the Star Trek screenplays written or co-written by Nicholas Meyer; Moore and Braga are simply not in his league. They’re the Lansing Lugnuts to his Toronto Blue Jays. We get technobabble about gravimetric distortions and confluxes of temporal energy instead of meaningful allusions to Shakespeare and Sherlock Holmes – dialogue that is so hard to render truthful that the otherwise skilled cast are left flailing and sounding like amateur dinner theater hams. (We are left to wonder at the substance of Leonard Nimoy’s extensive notes on the script as mentioned earlier.) In syndicated television like The Next Generation, writers are generally not allowed to write serial arcs where a story builds from one episode to the next because the networks buying the episodes want the freedom to air them in whatever order suits them. As a result, characters in syndication usually deal week-to-week with basic, surface problems that will have no lasting effect on them (Billy needs to study for his test but wants to go the baseball game instead! Dad wants to have a romantic dinner with Mom but keeps getting sidelined by his boss!) While Star Trek Generations tries to give us big events like the destruction of the Enterprise (in a sequence that is way too long and doesn’t advance the plot one millimeter) and the death of Captain Kirk, it handles them with all the gravitas of Marcia Brady worrying that she can’t go to the prom because she’s having a bad hair day.

We felt the death of Spock. It hurt. Even in hindsight when you know he’s coming back, The Wrath of Khan hits hard. That movie lets the emotions play out and follow us to the end of the credits and even into the theater lobby. With Kirk’s death, we just shrug and get on with it, as do the other characters, who are back to wisecracking in the very next scene as if the loss of the great and storied hero was no more relevant than the loss of a pesky hangnail. (Worse – Kirk’s death is juxtaposed with and given the emotional equivalence of Data finding his lost cat.) I don’t know whether the movie would have benefited from an extended eulogy and funeral scene, given that nothing in the preceding hour and thirty minutes had legitimately led us to that. Indeed, Star Trek Generations is a movie absent of consequence, refraining in every frame from asking us to dip deep into the emotional well, either because the storytellers simply aren’t that skilled, or because in its blatant desperation for the pat on the head, it’s afraid to. Spock’s sacrifice meant something because it was to save people we knew and loved. Kirk’s sacrifice (and that of the Enterprise herself) is to save two hundred and thirty million aliens we don’t know, don’t ever see, and can’t get worked up about. Generations also owes too much to the continuity of the TV series, dragging arcs like Data’s emotion chip, the Klingon sisters and even Worf’s promotion in front of audiences who should not be expected (or even asked) to remember exacting details of episode five of season four in order to understand the plot. Combine that with TV director Carson’s TV pacing and you get, sadly, what many critics of the time referred to this movie as: an extended episode of The Next Generation, and not even one of the better ones at that.

In his review in 1994, the late Roger Ebert made special note of the extreme low-tech climactic battle between Soran and the two captains, observing that it seemed to be drawn from old Westerns, and accusing the writers of a failure of imagination. And this was actually the second ending to the movie, re-shot in pickups months after principal photography after the first version, in which Kirk took a phaser blast from Soran to the back, blew chunks with test audiences. It does seem strange that with the broad canvas of the entire galaxy to choose from, this was the best they could come up with for the long dreamed-about meeting of our two storied captains, shoving it out in front of us and hoping that the spectacle of “SHATNER! STEWART! TOGETHER!” would be enough to keep us from picking out the numerous flaws (including the legitimate question of why, if Picard can leave the Nexus and go anywhere at anytime, he doesn’t go back a month and have Soran arrested, instead of only giving himself a ten-minute window?) Maybe Star Trek Generations was never going to be that great because there was too much riding on it; too many people with their own opinions of Kirk vs. Picard and how an onscreen meeting should unfold. The movie is not entirely without its charms: Brent Spiner is very funny as Data gets his emotion chip and becomes the comic relief, Stewart is typically brilliant and sells flimsy dialogue as though it were the most weighty words ever assigned to paper. The production gets more than its money’s worth out of John Alonzo who creates some lovely color palettes and brings fresh life to old cardboard sets. And as weak as the overall execution is, only the irredeemably cynical Star Trek fan doesn’t feel a few goosebumps seeing Shatner and Stewart together. But that old adage holds true: if it ain’t on the page, it ain’t on the stage. Poor writing is the downfall of Star Trek Generations, and we shudder to think at how bad the Maurice Hurley version was if this script was the one that beat it.

In summary: Watch “Yesterday’s Enterprise” or “All Good Things” instead.

Next time: The Next Generation crew stands on its own as Moore and Braga get it right on their second try, ably aided by actor-turned-director Jonathan “Two Takes” Frakes.

Final (Arbitrary, Meaningless) Rating: 1 1/2 out of 4 stars.

P.S. Happy Canada Day! 🙂