“We’ll definitely get a ball.”

Of all the things my father ever said to me in the ten short years he was in my life, that one resonates louder than the others, as if it were etched by laser into the very tissue of my brain. I can recall other moments, and wiser words offered on more significant occasions, but that one statement carries a deeper meaning. It’s a promise any father would happily make to his son, with every intention of keeping it even if doing so depended entirely on chance. What else would you say? Would anyone want to dim an eight-year-old’s innocent hopes with frank explanations of probability and odds?

The snared ball is the greatest prize a baseball fan can hope to claim. Financially it isn’t worth much, you can easily purchase one at modest cost from any vendor of sports equipment and yet for decades spectators at every stadium in every city have been leaping, diving and twisting themselves into pretzels to try to close confident fingers around that little, immensely important lump of cowhide and rubber. It’s not the thing, of course, it’s the connection to the game. Of being able to feel for one split second that you aren’t a faceless nobody in the crowd, but an integral part of the story you’re watching unfold before you. Some people, like the infamous Steve Bartman, have seen their desperate quest for a ball script them into the narrative with an odious lapse in judgment they’ll rue to their last days. For most, it’s just a matter of being in the right place at the right time, of sitting happenstance under the end of the arc of an errantly tapped breaking ball on the outside corner.

My father had been to the snow-blanketed, very first Toronto Blue Jays game in April 1977, and as soon as I was old enough to sit still for two plus hours it was my turn to accompany him to Exhibition Stadium every few weeks throughout the summer months, to find a place on the cold, chipped blue paint metal seats, with steamed hot dog, scorebook and tiny glove in hand, and watch the magic unfold on the bright green turf – hoping, as all kids did at that age, that the coveted foul ball might miraculously find its way towards us. Shortly before the start of the ’84 season, he and his best friend John decided to go in halfsies on seasons tickets to ninth row seats up from first base. John knew nothing about baseball (he intended to use his tickets largely to promote his insurance business), so my father was able to discreetly pick out the best games against the best teams with the best giveaways of Jays swag. He put this thick book of 40 pairs of slim cardboard tickets in my hand and stood back to watch my eyes gleam as my fingers rifled through them. I hope we catch a ball this year, I must have said.

“Oh, we’ll definitely get a ball,” he replied.

We had to, right? Going to that many games, it was just a matter of time and inevitability before say, Willie Upshaw or Damaso Garcia popped a lazy curve just over our heads and into our laps. And so we went. To contests held in both evening and afternoon, scorchers under the July sun and polar affairs in late September darkness. We baked, we were drenched, we froze, and still we went and we watched and we waited for that pop-up, both wearing gloves for the moment it was bound to happen. 1984 came and went, the Detroit Tigers stomped everyone in the league on their way to the World Series, and despite all of it we were still without what my little heart wanted most. The ritual resumed the following year, and we went again, sharing in the triumph of the victory in the AL East and the heartbreak of seeing the Kansas City Royals snatch it all away. But still no ball. We came close once during a night game: our seats were on the aisle and a foul did careen its way to about five steps above us, but despite my father attempting to imitate Kevin Pillar four full years before Kevin Pillar was even born, the ball slipped out of his grasp and into some other lucky sod’s hand. (My father joked with friends later on that I had recorded the play in my scorebook as E-Dad).

We didn’t go to as many games in 1986, and I don’t remember what the last game we saw together was, but it too ended with that promise still unfulfilled. There was probably a shrug and a “maybe next year” comment, and I don’t think I was even that upset about it. I was old enough to understand then that catching a ball was really down to luck and being in the right place at the right time. “It’s okay, Dad,” I’m sure I said. Besides, there were much more potent and lasting prizes accumulated from all those games – memories, emotions, and precious shared time with the man I admired most in the entire world.

“We’ll definitely get a ball.”

Five months after the end of the ’86 season, he was gone.

He was gone long before Toronto had heard of Roberto Alomar or Joe Carter. He wouldn’t see the opening of the SkyDome, nor the brushes with greatness that were the AL East championships in ’89 and ’91. He wouldn’t see the glories that were ’92 and ’93. And he wouldn’t get to see his son walk onto that field (with two hundred other red-coated marching band members) to play the national anthems for a game attended by then-prime minister Brian Mulroney and President George H.W. Bush. Weighed down by a fifty-pound bass drum harnessed to my chest I took a breath and soaked in the persistent, bass-clef hum that hovers in the stadium air, thinking briefly about the voice that was missing. the one that would be cheering the loudest, pointing and boasting to everyone in earshot that “that’s my son!” The one who’d still doggedly bring his glove to each game because he had an old promise to keep.

After having found my way back to baseball again these past few years I’ve wondered on occasion how he would have reacted to the strike of ’94 and the Blue Jays’ ensuing two decades of irrelevance and ugly uniforms. If maybe there would have been a few arguments here and there about the importance of remembering and savoring the purest parts of the game and the impact it can have on the heart, rather than letting oneself be disillusioned by salary disputes and steroids and endless losing seasons. I wonder if we still would have found ourselves in those first-base-line seats every other week staring hopefully towards home plate and tensing fingers inside mitts at each crack of the bat even as the crowds thinned away. My father was many things, but not for one moment could he be accused of harboring the remotest hint of cynicism – hence the deliberate choice of the word “definitely.” It was going to happen, it was just a matter of time and patience, and of never losing hope.

Fast forward to May 26, 2017.

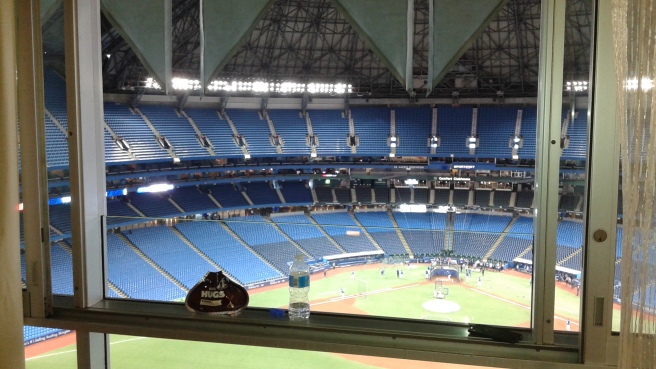

The reviled Texas Rangers are in Toronto for the first meeting between the arch-rivals since Rougned Odor threw past Mitch Moreland to throw away their 2016 season. A month or so earlier, my wife has the suggestion that we celebrate our upcoming tenth anniversary by renting one of the rooms in the Renaissance Hotel overlooking center field for the night. It’s a lot of money, but we need the break after a stressful couple of months, and besides, it’s one of those bucket list experiences that every Jays fan should try at least once. So we take the plunge. The timing of the game she picks turns out to be serendipitous, with Josh Donaldson and Troy Tulowitzki each scheduled to return to the lineup for the first time after month-long stints on the disabled list. I book the afternoon off work and we make our way down to the stadium, check in, grab a Starbucks and take the elevator up to the fourth floor, after signing the waiver promising we won’t do anything lewd within view of the public or worse, chuck anything onto the field. The view is incredible: staring directly back towards home plate, the tails of the championship banners dangling just above our window. For the first time, I’ve hand-painted a sign to bring to the game; it reads IT’S OUR 10TH ANNIVERSARY – GO JAYS GO! I tape it to the glass and lean out the window to watch the Jays take batting practice. The air smells of air conditioning and oil, and even empty seats thrum with the anticipation of the contest to commence a few hours hence.

It’s kind of hard to see facial features, but I can recognize the haircuts and the batting stances. Donaldson, Tulowitzki, Kendrys Morales, Jose Bautista and Ryan Goins are each taking their turn smacking balls into the outfield. Some dude in a suit with a shock of white hair is wandering around the cage chatting with each as they finish: the one and only Buck Martinez, the same guy my father and I use to watch behind the plate at the Ex. Directly below me, Blue Jay pitchers are taking warmup tosses with one another. Marco Estrada is doing a series of hard sprints from left field into center, and as he finishes each he tilts his head up. Like a starry-eyed six-year-old I wave at him each time, and on the fifth sprint he gives me kind of a half-assed arm shrug back, as if to say “bugger off mortal, I’m in game mode.” Even though Mike Bolsinger is scheduled to start tonight, Estrada remains all business.

The pitchers finish their throws and four of them congregate in center to retrieve the balls the sluggers are knocking their way. From our perch above it’s still hard to distinguish features, but numbers on warmup jerseys help. Dominic Leone, J.P. Howell, Aaron Loup and Jason Grilli (easy to pick out with his longer hair) stand there chatting about whatever it is ballplayers chat about when the cameras are absent. As Bautista knocks balls into the still-empty outfield seats and the WestJet Flight Deck, Grilli’s attention wanders and he turns around to look up. This way. I wave. He waves back. He sees my 10th anniversary sign. He points it out to Aaron Loup. Grilli’s been kneading a ball in his hand, and he holds it up as if to offer it to me. I give a thumbs up. Grilli reaches back and lobs it up, high, towards our window.

THUNK.

Off the glass just to the right. Way outside the zone. Ball one, maybe. It tumbles back to the turf.

Grilli gets another ball and throws again. This one misses to the left. You can’t fault the guy for trying, but it’s starting to look a bit hopeless. We’re really high above the field, and it’s not as if he can afford to burn his velocity and control on a souvenir for a fan when he needs to save it for a possible eighth inning against Mike Napoli et al, you know, the situations he gets paid $3 million a year for. The third try is closer, but still off the mark. I shrug at him, assuring him that it’s okay, that I appreciate the effort.

But the Grilled Cheese is undeterred, and he goes for a fourth attempt. Here it comes. Up, and up, and closer. It hovers just outside our window, and time freezes it in place, tantalizing me. Here it is, that invaluable prize the little boy in you always wanted. It will never be closer than it is right now.

I thrust trembling arms through the window, and shaking fingers close tight.

I’ve got it. Holy shit, I’ve got it.

Part of me can’t believe it’s just happened. Quickly, I wave and give Jason Grilli a big thumbs up, and call out “thank you” even though he probably can’t hear me. Then I turn away from the window, open my hand and look down. It’s a lot smaller than I thought it would be. It’s scuffed with blue and brown from its journey from the bat across the dirt infield to Grilli’s glove to my hands. So little – and such a big deal all at the same time. A lump rises in my throat and tears start to pool at the corner of my eyes. A thirty-three-year-old promise, fulfilled as someone now long gone knew it always would be. Maybe you can imagine that somehow he was guiding that last throw from Grilli. Maybe it was all a coincidence. But it doesn’t matter. By whatever means you want to believe, it still felt in that moment like a final gift from father to son. A reminder that cynicism is nothing next to the enduring power of hope. The same intangible quality that keeps us invested in baseball no matter how dark the world outside gets, no matter how many runs the opposition piles up. Hope can be found in the smallest of things, even in a modest collection of 216 stitches.

“We’ll definitely get a ball.”

We definitely did.

Thanks, Grilled Cheese.

Thanks, Dad.