I wasn’t there at the beginning. He crept unheralded onto the roster during my long night away from baseball and the team my father had taught me to love. I wasn’t there as he transformed himself from a perennial journeyman castoff and marginal bench bat into one of the most powerful, most feared, and most significant hitters in the entire sport. I – along with many others, judging by the endless rows of empty seats in the old highlight reels – wasn’t there, for the most part, to watch him become Jose Bautista.

But I, along with 47,393 others, and probably a great number more who wished they could have been, was there for the end.

As I noted last time, this was a crummy year for the Blue Jays, the metaphorical bill coming due for two most remarkable, franchise-reinvigorating seasons full of individual moments to spark debate and storied recollection for years to come. It’s never easy to cope with the head-pounding hangover that follows, or to settle into the realization that maybe this ball club hasn’t quite made it over that maddeningly elusive hump that separates perennial contenders from perpetual also-rans. Maybe, like the Minnesota Twins, we’ll have one bad year and be right back in it the next. Whatever happens in 2018, it’s hard to nestle into the idea that No. 19 won’t somehow be part of it. He has ingrained himself into the soul of this team, that bearded visage almost as eponymous for the Toronto Blue Jays as the bird in profile stitched into every uniform.

Somehow, it was easier to get over Edwin Encarnacion leaving. We went through the five stages of grief pretty fast, soothed somewhat by how well Justin Smoak performed in his place at first base. I was away from the game during Roy Halladay’s tenure, so he never meant as much to me as some of the guys in the 80’s I grew up watching, but maybe it was just as hard when he departed for Philadelphia. At least you knew Doc would land on his feet, and indeed, he made some of his biggest contributions only once he was sporting a P on his cap.

We don’ t know what the future holds for Jose Bautista. As he looks at 37, his fielding a shadow of what it was and the pop largely quieted from the singular bat, the thought of him reduced to a minor-league let’s-give-it-a-try deal to DH with a sub-par franchise somewhere else is heartbreaking.

That’s not how a legend is supposed to go out.

Blue Jays Nation’s Andrew Stoeten wrote a great piece a couple of weeks ago about how baseball seems to have piled itself collectively onto Jose Bautista and how despite the load, he’s never broken. I’ve never quite understood why the mythos of Bautista-as-villain has been perpetuated, and the only “rationale” I can find is that maybe folks just don’t like being on the receiving end of one of his home runs. You’ve heard the boos that rain down on him in every opposition ballpark (except maybe Seattle, simply because it’s flooded with Jays fans) and the snipes from jackass GM’s who whine that they wouldn’t want to sign him because their fans don’t like him. You’ve seen the douchewad managers who order their pitchers to throw at him, or the childish players who dispense with words and just out-and-out take swings at him. That’s what you get, it seems, for being exceptionally good and injecting, God forbid, some actual panache into how you play a “stately” sport that can at times bore people to tears with its mountains of algorithms and acronyms and robotic players possessing nary a discernible trace of personality.

Jose Bautista has always been larger than life. I’d rather have – and the dirty secret is, most fans would rather have as well – a once-a-generation shining light than a legion of statistically competent monks shuffling in and out of the clubhouse. You know, the types who play well enough, but no one ever wants to buy their jersey, or would ever sing their name out along with 40,000 friends after an instant of triumph. Cleveland has a bunch of dudes like that, they won 102 games this year, and day in and out in the regular season they can’t fill their stands. No one cares. Because none of those guys has a flicker of what Bautista simply owns.

Jose Bautista is the kind of guy you’d want to make a movie about.

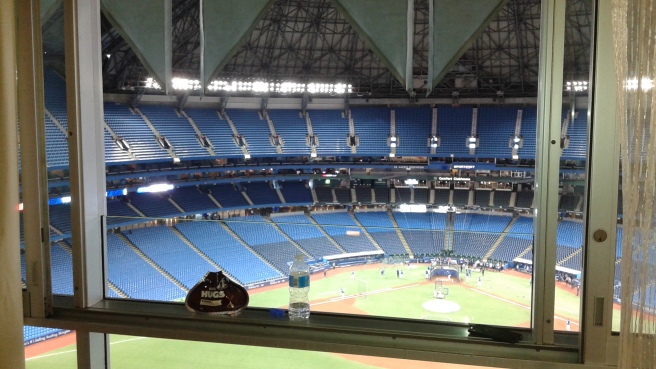

It’s fitting, then, that his last game in Toronto as a member of the home team had its own cinematic quality, and I’m lucky I got to witness it from five rows above home plate – just behind where Geddy Lee usually sits and keeps score. I bought a program, but didn’t bother with a pencil. I didn’t want my head buried in scribe’s work today lest I miss something special on the field.

The roof stayed closed until after 12:30, to hold off this atypical late September heat. Improvised banners dangled or were hoisted everywhere, saying goodbye, saying thank you, or making obvious predictions about a future anointing to the Level of Excellence. When a crack of sunlight crossed center and the panels began to slide back to the sound of the hip-hop pumped in by the stadium’s resident DJ, it was like the gradual unveiling of a Broadway curtain on the closing night of a show. Of course, you weren’t exactly sure how the show was going to go down. There was nothing riding on this game, the second Wild Card berth long having slipped out of reach. Maybe it mattered more to the opposition Yankees trying to catch the Red Sox and avoid the dreaded do-or-die one game playoff. It didn’t matter much to the talkative Yankee fan named Jonathan sitting next to me, who was in town on business and decided to grab a single ticket to hopefully see Aaron Judge sock some dingers.

It mattered to the rest of us, though. We wanted to see an acknowledgement of our hero. Baseball was dead in this town – pushing up the daisies, running down the curtain and joining the choir invisible dead – and he had cast his eye upon the empty blue seats and said no, I’m bringing it back. Maybe moreso than anyone else, he had brought it back.

Most of all this day, we didn’t want to see him fail.

The first actor took the stage. Marcus Stroman emerged for his warmups wearing an old-style black Bautista jersey, and we cheered. We knew then that they were going to get it right, that everyone down on the field knew the significance of this game as much as we did in the stands. The players let Bautista run out onto the field alone, his stride strong and determined, and we rose to our feet, careful not to waste a single of these last opportunities to let him know, here in the friendliest of confines where he’d never hear so much as a titter of disapproval directed at him, exactly how we all felt.

Heroes are few and far between in this day and age, when we are inundated hourly with relentless updates on the worst of us elevated to the maximum level of their incompetence and making the world suffer for their inadequacies (my new favorite word is kakistocracy – look it up). It still seems silly, though, to assign the concept of heroism to men who get paid more in a year than we’ll earn in our lives to play a game for six (and if all goes well, seven) months. Yet if you reflect on our intrinsic need for heroes, and the ability of athletes to unite thousands in a single, blazing moment of ecstatic, unifying glory – like what happens when a fastball down the middle connects with the barrel of a bat, and time and sound halt for a microsecond before the telltale crack – and a veritable supernova of unleashed excitement follows – how can you not come to think of the men who generate these moments in those terms? Chances are you’d probably hate the guts of a majority of the other people in the stands with you if you knew them personally – what quality do you ascribe to someone who can compel you to set all of that aside and come together en masse with one purpose, one intensely shared passion; an instant when you know that everyone around you feels exactly the same way?

Bautista must have sensed it, and he fed off it. Instead of looking like the flailing strikeout magnet he’d been for the majority of the season, there in the haze of an aroma of sunblock and french fries and humidity fogging the camera lenses we were all trying to use to capture these important final hours, he stepped into the box with the hot winds at his back. He turned on the first pitch he saw and deposited it in front of Aaron Judge for a solid single. The next time up, Yankees starter Jaime Garcia avoided giving him anything to hit, and he strolled to first on a walk, to be cashed in later by Russell Martin’s bases-clearing double.

When Bautista came to the plate with the bases loaded later in that game, the stir that had been building in the park began to crest; things had been going well so far, the Jays were out to a comfortable lead and Judge hadn’t done anything yet. It was a growing recognition that maybe the gods of baseball were crafting the narrative to a conclusion drawn from The Natural. The right man at the right time in the right place, one last time. And just like we all did when the count went to 1-1 in ALDS Game Five, we took to our feet, drew a breath and shared one collective thought, 47,394 strong.

Please, don’t let him fail.

The pitch came.

The leg kicked, the barrel turned, and–

Off it went. Not to the seats, but safely into right field again. Another single.

A runner crossed the plate. Notch another in the RBI column. And doff your cap to the man standing at first, mission accomplished for this inning.

It wasn’t legendary. It wasn’t really even spectacular.

But it was enough.

I recall wondering if maybe, when he came to the plate for what would likely be his final at bat in the game, if Dellin Betances, on the mound for the Yankees at the time, might just toss him a “Sam Dyson Special” to give Bautista one last chance to do what he had done almost without parallel for ten years. (Don’t tell me pitchers last year weren’t going easy on David Ortiz from time to time.) But the Bronx Bombers still had their eye on the division title, they’d Judged their way back into the scoring in this one – much to the delight of young Jonathan to my left – and they weren’t inclined to give anything away. So Jose Bautista’s final plate appearance in Toronto would be a forgettable pop out into foul territory.

However, it was probably one of the only times in baseball anyone has received a standing ovation for doing that.

The best had truly been saved for last, though, and when manager John Gibbons lifted the man of hour for Ezequiel Carrera with one out in the ninth inning, a 9-5 lead safely in hand, the warrior returned from the field with his shield intact. When he paused to hug each of the teammates he encountered on the way back, the tears started to well. Yes, contrary to what Tom Hanks would have you believe, sometimes, there is crying in baseball – tears that are earned, and shared, and cherished.

With all of our remaining energies, with our palms pounding furiously against one another and shaking the very walls with our raised voices, we saluted him.

He waved back.

Ted Williams, famously, didn’t. Jose Bautista did.

Some gods do answer letters, Mr. Updike.

Roberto Osuna sent the Yankees packing, he and Martin did their end-of-game knock-knock-and-dab, but eyes diverted immediately to just outside the dugout, where Bautista was speaking with Sportsnet’s Hazel Mae. I didn’t learn what he said, nor the emotions that he chose to reveal, until much later at home; instead I snapped the photo above and remained in my seat, watching the field clear and the crowds file out and listening to a deep silence descend, knowing that it wouldn’t lift until the end of next March and that an important, needed piece of that picture wouldn’t be there on that day. That the crowd would be full of fans wearing jerseys bearing a name and number now extinct and relegated to the past.

It’s appropriate that regardless of weather, the roof at the Dome is closed soon after the game concludes; it’s the curtain being brought down on the show. We yielded finally to the inevitable and began the trudge back to the car, satisfied in the victory, satisfied that our hero had done well this day, speculating on the ever-churning well of what-ifs that might mean this wasn’t really the end. If it had to be, then it was fine. Perhaps not the ending doused in the champagne bubbles of a World Series after party, but an ending of dignity, of respect, and of gratitude. The quiet, European cinematic ending.

The Toronto Blue Jays will win another World Series soon enough, and while he won’t be in the lineup that physically accomplishes the ultimate goal, Jose Bautista will have been an integral part of painting the way. Against odds, against expectations, and against an ocean of doubt and the clucking of baseball’s mother hens, he made himself, through sheer force of character and will, into a legend in these here parts. Bautista’s work made the team a contender again, made great players want to play here, and made disillusioned fans pour back in through the gates in ever-swelling torrents, even in a losing season. Those who come afterwards will be fated to be compared to him and what he achieved.

This day, September 24, 2017, he did not fail. Over ten years, he never truly did. He went out and played and got the crap kicked out of him and kept showing up and kept trying, and he was rewarded and he was reviled and he kept going, with all the grit and mettle you come to expect from the finest people to ever pick up a bat and a glove. He has nothing left to prove to the people of Toronto, nothing more owing on that contract with the fans. It is left to us, then, to ensure that the memory of what he did for us remains strong, as the feats of Dave Stieb and Roberto Alomar and Joe Carter and others still do these many years later. That these unifying little slices of time, the where-were-you-whens, will go on and never fade away.